Posts Tagged social photography

Instagram: a teen-toy or the new reporter tool?

Posted by leagloor in Technology on November 26, 2012

“Instagram photos cheat the viewer!” Nick Stern’s claim, published in February 2012 on cnn.com, came as a bombshell, engendering pros and cons-reactions in the journalism and photo-reporting world. Who’s right? Let’s have a look!

With more than 30 millions of users and about 150 photographs posted (see article on Wikipedia), the photo-editing and social-networking app Instagram can be described as one of the most successful Smartphone tools. Among its users; teenagers, adults, singers, actors, politicians and, of course, journalists!

Yet the journalistic use of Instagram in a professional perspective has created a huge debate on the web since last February. The vexed question: can journalists and photojournalists honestly use Instagram as a professional tool, to cover a war or a political meeting, or has it to remain a “toy” only good to post pictures of your breakfast or your new nail-art?

|

Cheating with reality?

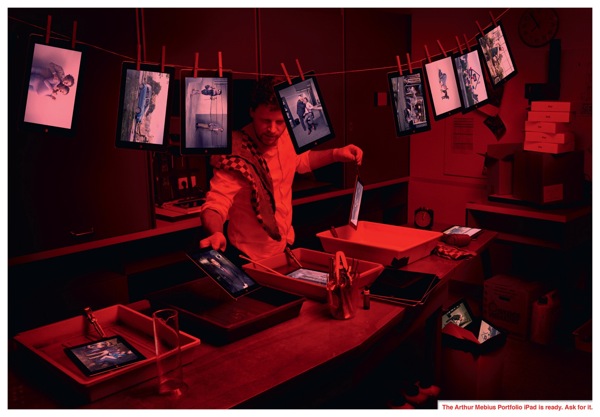

For some photographers no hesitation, Instagram has nothing to do with information and journalism. Here are some of their main arguments. But before, here you go with a video that shows you how Instagram works and what are its main features:

Filters and fake emotions

Photographs bring emotion, related to the subject, to the viewer’s history but also thanks to the way the picture is taken. Regarding this, the anti-Instagramers are clear: Instagram kills the authenticity, creativity and originality of your pictures.

For Nick Stern (see the complete article here and his website here), American news photographer and first anti-Instagram pamphleteer, the pictures taken with the app do not communicate real emotions, conveyed by the photographer, as it should. “It’s the work of an app designer in Palo Alto who decided that a nice shallow focus and dark faded border would bring out the best in the image”, he claims, “The image never existed in any other place than the eye of the app developer”.

“The greatest photographs are created in the mind of the photographer and not in the workings of the camera.” Nick Stern

Moreover, with 14 different filters, the variety of pictures is indeed quite large however rather limited. According to its accusers, Instagram creates therefore photographic standards, which enchain the users, kill their creativity and prevent them from expressing their emotions.

But was it not already the case with silver films? Indeed, during the development process, the photographer could use different chemical techniques such as cross-processing and could therefore add something external to the picture.

Aesthetics against information duty

Showing reality objectively is one of the main goals of any journalists. For the anti-Instagramers, using an app that adds effects on a picture in order to make it look fancier or nicer does not fit the profession ethics. That is why Nick Stern says that “Every time a news organization uses a Hipstamatic or Instagram-style picture in a news report, they are cheating us all”.

However aesthetics is a part of photography anyway such as subjectivity. Photographers are dealing with image and cannot completely distance themselves from the visual dimension of their job.

As Joerg Colberg, an American photographer says “We all know that all photography is fiction: as a photographer you make choices, which influence the photograph enough for it to be more of a fiction than a fact. […] But the photojournalist’s task, no actually the photojournalist’s duty is to minimize the amount of fiction that enters her/his photography. […] The problem with InstaHip in this particular context is it adds a huge amount of fiction to photography, simply by its aesthetic” (see the complete article here).

News Trivialisation

Another problem raised by the accusers is that the majority of the Instagram pictures deal with the users’ every day life: meals, hobbies, fashion, cosmetics, friends, family and pets. Mixing serious news pictures with these trivial subjects minimizes their value and their informational impact.

“Since in the dominant context, people’s social lives, InstaHip photographs are usually not seen as particularly relevant, once you use InstaHip as a photojournalist you’re applying that same kind of thinking to your images. You’re trivializing your message.” Joerg Colberg

Why so unserious?

Maybe the solution would be to create a parallel network, which would share the same technical features and would be exclusively destined to news companies, a kind of Infostagram! But we will come back to that later.

The Like button tyranny

As other social networks, Instagram allows the users to share their pictures on other social medias such as Facebook and Twitter and proposes a comment option and a Like button.

American panelists wondered to which extent “Instagram’s Like button, combined with the image filters, has turned the service into performance art, with people trying to rack up Likes for the most aesthetically striking images” explains Steve Myers in his article on Instagram (see the complete article here). A sort of photographic social desirability!

As we will see later, these social network features can also be positive for journalists. In the mean time, to read more about the Like-culture problematic, click here.

Vintage overdose

You can see it in fashion: vintage is trendy! And photography is no exception to the rule. Instagram, with its Instamatic and Polaroid-inspired effect perfectly incarnates this trend (see this article here). But as Jean Cocteau said “Fashion is what goes out of fashion.” Thus, the risk that Instagram becomes outmoded is real.

What risk for journalism then? Since Instagram becomes has-been, the information broadcasted on it will not be seen as relevant by its users or its ex-users. The value of information will be at stake.

Moreover, is not information supposed to be related to the here and now, to the burning issues and not focused on the past?

Instamatic Kodak 100, 1963 |

Polaroid One Step, ’80 |

Connecting people?

Does Instagram look like the Devil to you now? Fortunately some positive and helpful aspects can also be highlighted, all related to the social dimension of the app.

Information network

As already said, Instagram is not only a photo-editing app, it also allows the user to create an extended network, to follow people and to get followers. Videos on Youtube actually show you how to be followed by the maximum of users. Do you remember what we have said about the Like button tyranny?

More seriously Instagram can become a real information feed, through the channels of news companies or through the topics dealt with on the official blog of the app (see here). However, at the moment, the media channels remain extremely poor and unfed. The only one which seems active is the CNN’s, perhaps because of its US origin and destination. Here are some examples taken from Webstagram, the Internet viewer of the app.

One of the rare successful examples of use is the covering of the New York Fashion Week 2012 by the New York Times. The journalists present on the site provided 450 pictures through the account created for this occasion, visible here. With 156’319 followers, the operation was a real success.

|

|

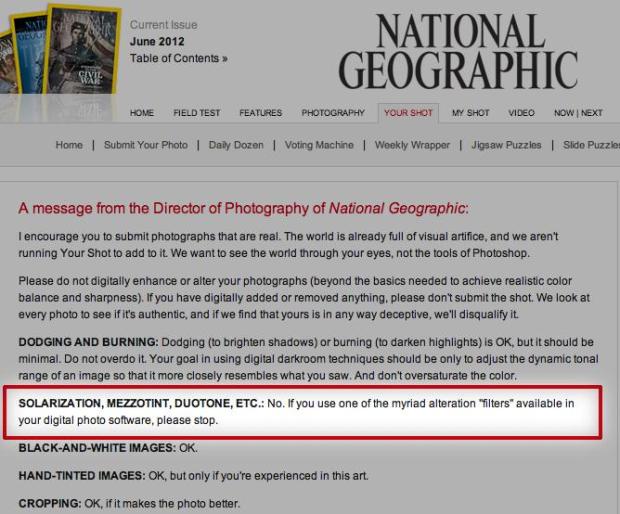

Another example: the National Geographic launched a blog fed with climbers’ Instagram pictures called “Field test – On Everest”. The Instagram feed of the magazine, visible here, is also well provided with pictures.

However the company seems less tolerant regarding the pictures sent by its readers. In a message on the company website, the photography director encouraged the National Geogrpahic readers to avoid sending them modified pictures:

This desire of authenticity and objectivity matches the cons arguments presented previously regarding Instagram.

The non-professional Keystone

If the National Geographic had a really ethical reaction regarding photography, this is not the case for some other medias. Indeed Instagram can be used as a kind of a non-professional Keystone.

Let’s think about several showbiz articles written by the 20minutes about Rihanna’s tattoo or Kim Kardashian’s look. The information comes directly from what the celebrities post on Instagram as a primary source. Even if we are talking about famous people, this is what we call crowdsourcing or UGC (User Generated Content).

In a more serious perspective, a new app has been developed, called “Signal”, a mix between Instagram and Foursquare. With this app, you can post pictures and geolocalize them.

Normal citizens and journalists will thus be able to get informed of the events happening in their country or their area. What happened with Twitter during the Arab Spring could also happen thanks to photographs (see complete article here).

Democratisation of photography

One of the main arguments against Nick Stern’s article was that his vision of photography was elitist. Let’s think about Mathew Ingram’s article (available here) who vividly criticizes this vision.

Likewise, the photographer and photography teacher Richard Koci Hernandez praises the new possibilities of interacting with the audience offered by Instagram: “More people are now being exposed to my journalism than ever before […] Now I have access to literally the entire world.” (see complete article here).

Thus, for Instagram-defenders, using this app is also a way to have access to a form of art production, which was by now saved for professionals and artists. But can we honestly put on the same level the technique required by an SLR camera manipulation and the use of a mobile phone?

A matter of perspective

As we have seen, no categorical answer to the Instagram problematic can be given. Asking what a relevant photograph or a worthy photographer should be requires also to ask what photography is. A hobby? A job? An art? The three of them? Maybe the answer lies in the context or the personal perspective in which the picture is taken.

Let’s think about Benjamin Lowy’s work in Afghanistan. He used Instagram but did not betray what the journalist Alex Garcia calls “the vision and mission of photojournalism – [he is] applying a creative aesthetic that adds meaning or accessibility to [his] images” (see complete article here).

Anyway we should not forget that, Instagram or not, photography is always a matter of choice. By then, watch the birdie!

By Lea Gloor

La tragédie humaine : Comment en parler ?

Posted by violetaferrer in People, Various on November 18, 2012

Camp de Korem. Ethiopie. 1984

« La pauvreté, on s’en remet. La misère c’est une chose atroce, qui coupe les jambes et la tête.

La misère, elle est tragédie » Michel Ragon

Sebastião Salgado : De la réalité à l’art. Né au Brésil en 1944. Photographe engagé, il a parcouru plus de 100 pays pour dénoncer les injustices et présenter la réalité en noir et blanc dans un profond réalisme magique.

Reportage photographique de 1984 à 1985 au Sahel publié dans plusieurs journaux internationaux : L’opinion publique prend connaissance d’une manière inédite de la sècheresse, de l’exode de la population rurale et de la guerre civile provoquée par la famine. Une région qui, encore de nos jours connaît la sous-alimentation extrême. L’organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture, le FAO fait un appel urgent pour réagir à cette crise alimentaire.

Reportage photographique au Sahel

1984, cette région d’Afrique subit une sécheresse des plus désastreuses ainsi qu’une famine qui tuera plus d’un million de personnes et conduira à l’exode de milliers d’autres. Salgado, un des photographes documentaires les plus célèbres de tous les temps, photographie cette cruelle réalité dans la plus grande beauté artistique. Sa photo «Camp de Korem. Ethiopie » ci-dessus, artistiquement, est un exemple de pièce d’art presque biblique, anachronique, impossible à situer dans un moment historique. Sous cette lumière qui pénètre entre la nature et autour de cet arbre ancestral, se trouvent des centaines de personnes dont la souffrance est immesurable. Les photographies de Salgado ont la caractéristique de réunir deux mondes apparemment opposés : la tragédie et l’art.

Pour connaître sa biographie et tous ses travaux, visiter le site Internet : http://www.amazonasimages.com/

Instrumentaliser la misère pour créer de l’art?

Il y a d’une part, ceux qui revendiquent « l’art pour l’art », postulant l’autonomie de l’art et rejetant tout engagement social ou politique, valorisant ainsi le caractère poétique de celui-ci. D’autre part, il y a ceux qui défendent « l’art pour le changement social » où l’art serait un instrument pour le changement de la société, et par lequel l’artiste est appelé à réagir et être un acteur précurseur de changements.

Salgado explique que ses photographies sont une manière de présenter le monde, dont la réalité n’est pas en noire ou en blanc, mais un amalgame infini de gris. Où parmi la misère, il peut y avoir la beauté et parmi la richesse, il peut y avoir la monstruosité. Salgado explique dans une interview « Dans le monde où nous vivons, nous sommes tous concernés, nous ne pouvons pas fermer les yeux, ne pas participer à un changement, et la photographie est un langage qui nous aide à comprendre le monde, elle n’a pas besoin de traduction, elle est universelle »… . UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism présente une conférence dédiée à Sebastiao Salgado où il est question de son art, ses inspirations et sa manière de concevoir et interpréter le monde.

Comment parler d’exil, de faim, de misère dans les médias?

Le mandat, la responsabilité des journalistes est d’être des porte-paroles des plus démuni(e)s, de faire connaître au public des réalités lointaines, et participer à la compréhension du monde. Et pour les plus héroïques, lutter pour un changement social. Aux journalistes, chiens de garde de la société, défenseurs de la démocratie, de la liberté d’opinion, et d’une utopique objectivité, une question se pose : Comment présenter la faim à ceux qui comme vous ont l’estomac bien rempli ?

Salgado a choisi de le faire avec des photographies solennelles. Certains pensent que son travail est abstrait, s’approchant plus du travail artistique que journalistique. D’autres pensent qu’il a une manière propre d’interpréter les faits, générant un impact sur la société, la sortant de son impassibilité quotidienne pour la mener dans un monde où se marient horreur et beauté, avec une subtilité magistrale.

Est-ce qu’il existe une manière correcte de parler de la misère humaine ? Il n’existe certainement pas une manière politiquement correcte de faire. Il existe un protocole, un cadre déontologique à respecter : raconter véridiquement les faits, être rigoureux, faire recours à plusieurs sources, confirmer et contraster les informations etc. Il y a des guides pratiques qui expliquent tout cela. Pourtant, il est plus complexe de choisir la forme, la tonalité, l’émotion, l’angle, la manière de présenter la réalité, la souffrance et joie des autres, surtout quand personne n’aime voir ni entendre parler de la misère.

La famine, sujet d’actualité

Jean Ziegler, rapporteur spécial des Nations-Unies pour le Droit à l’alimentation de 2000 à 2008 explique dans son dernier livre : « Toutes les cinq secondes un enfant de moins de dix ans meurt de faim, tandis que des dizaines de millions d’autres, et leurs parents avec eux, souffrent de la sous-alimentation et des terribles séquelles physiques et psychologiques. Et pourtant, l’agriculture aujourd’hui serait en mesure de nourrir normalement 12 milliards d’êtres humains. Soit près du double de la population » (Destruction Massive, géopolitique de la faim, 2011).

La manière de présenter la tragédie de la famine est sans doute un questionnement obligé : La famine est de loin la principale cause de mort de déréliction dans le monde. Mourir de faim est extrêmement douloureux, une longue agonie qui entraîne des souffrances physiques et psychiques intolérables. Les médias ont donc l’obligation de parler constamment, infatigablement, et de toutes les manières possibles d’une des plus grandes causes de mortalité dans le monde : la faim.

«Aujourd’hui, un enfant mort de faim, est un enfant assassiné » Jean Ziegler.

Si vous souhaitez rester informé à ce sujet, comprendre ou agir pour lutter contre la faim dans le monde, suivez les mouvements : En finir avec la faim ou SOS Faim.

Que pensez-vous des photographies de Salgado ?

Pensez-vous que les médias parlent assez de la famine dans le monde ?

Avez-vous des idées pour lutter contre la faim ?

« El mundo nada puede contra un hombre que canta en la miseria ».

« Le monde ne peut rien faire contre un homme qui chante parmi la misère »

Ernesto Sabato

Violeta Ferrer